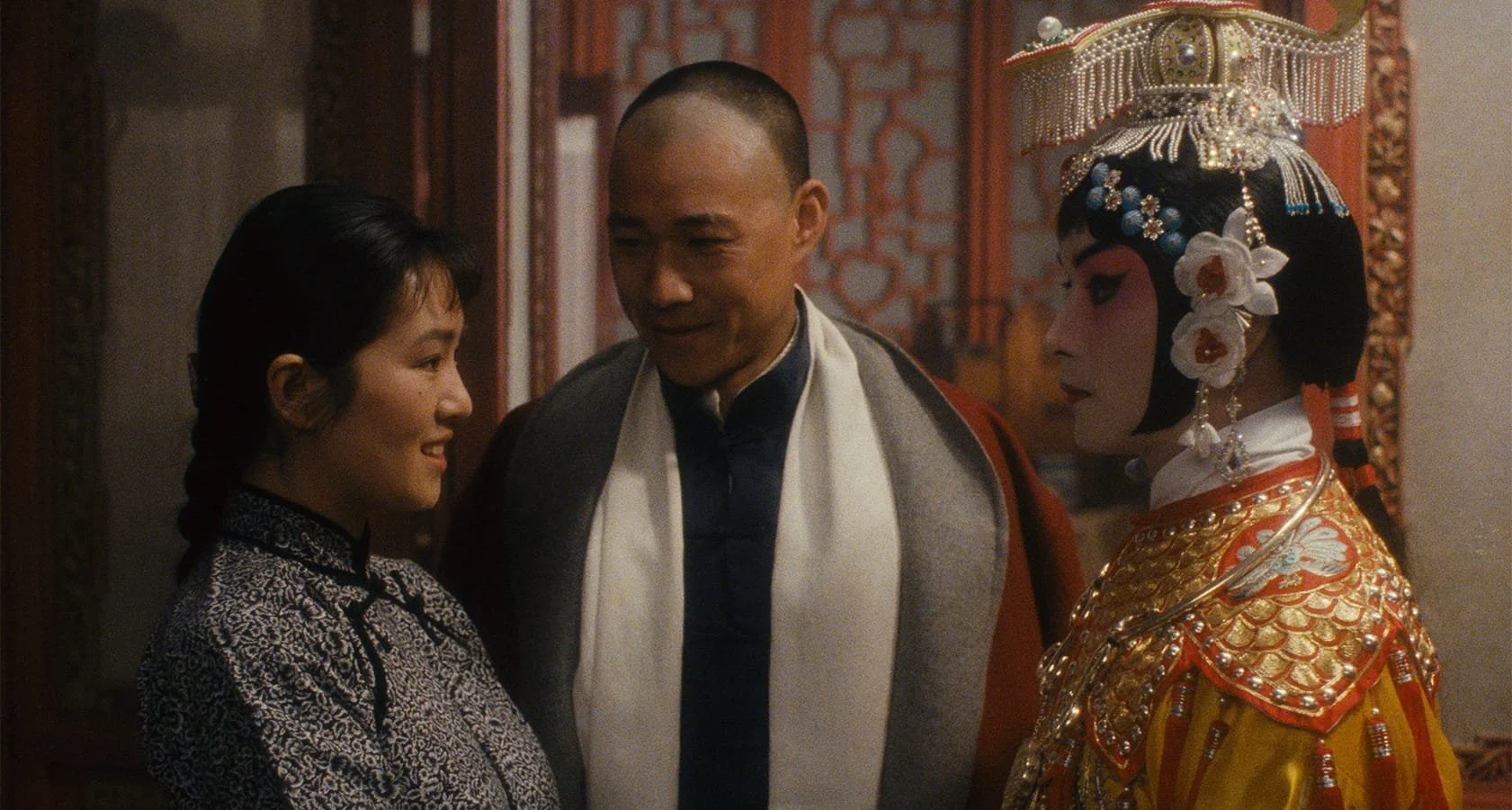

Farewell My Concubine | 1993

Courtesy of The Criterion Collection.

Upon its release in 1993, Chen Kaige's Farewell My Concubine became the first Chinese film to win the coveted Palme d'Or at the Cannes Film Festival, a prize it shared with Jane Campion's The Piano in a rare tie. The film was banned and censored both in its native China and in the United States thanks to Miramax's Harvey Weinstein, who reportedly cut around 20 minutes from the film's theatrical cut, only to release the complete version on home video, which remains intact to this day.

The film deals quite frankly with homosexuality for 1993 - a topic just as taboo in the United States as it was in China, although what Harvey Scissorhands' issues were aren't really documented, and heavy handed cuts were something of a Weinstein speciality. Farewell My Concubine is essentially about a love triangle, following the two boys who grow up studying Beijing opera in a camp for young actor, and the woman (Gong Li) who eventually comes between them. Cheng Dieyi (Leslie Cheung) is a waifish boy brought up to take on female roles (Beijing opera, like Shakespeare, was historically performed by men), while his friend Duan Xiaolou (Fengyi Zhang), his one friend and fierce protector, takes on the traditionally male roles. Their dynamic shifts greatly when Xiaolou falls in love with Juxian (Gong), a former prostitute whose presence in Xiaolou's life threatens Dieyi's carefully constructed fantasies and causes him to lash out in anger.

Much has been made of the gay nature of Dieyi's feelings for Xiaolou, but I was most struck by its heavily gendered overtones, suggesting that this was much more than just a man in love with another man. Dieyi particularly struggles with one line in the titular opera - "I am by nature a boy, not a girl," often flip flopping the terms and drawing the ire of his abusive master. Because he is a boy, he knows Xiaolou can never love him the way that he does, despite the feminine figure he cuts onstage. He desperately wants to become his character, to be the wilting concubine to Xiaolou's dashing king. The hatred he feels toward Juxian isn't as much anger as jealously and resentment - she is what he can never be, and because of that she gets the one thing he can never have.

Courtesy of the Criterion Collection.

Farewell My Concubine is not an explicitly transgender story, but I think an argument can be made that its characters and themes are grappling with something that they do not necessarily have the words to express. While the film takes us on an epic journey through 20th century Chinese history, from the Japanese invasion to the Cultural Revolution, the struggles of these three people one the course of the century becomes a kind of microcosm of the struggles of the Chinese people, at once existing apart from and as a product of the social upheaval going on around them.

Chen emerged from what is known as the 5th generation of Chinese filmmakers, a group that also includes Zhang Yimou (Raise the Red Lantern) and Tian Zhuangzhuang (The Blue Kite). It was the 5th generation that really began to broaden the appeal of Chinese cinema beyond mainland China (Zhang has especially enjoyed widespread Western success with films like Hero and House of Flying Daggers). Their work is also marked by a sumptuous visual style that divulged from the realism of the more directly political works of many of their predecessors. Farewell My Concubine is an often breathtaking film, its delicate and tremulous beauty coming to life in Criterion's new 4K edition. While much of the supplemental material focuses on its depiction of Chinese culture over its queer undertones, I think it's a film that stands ripe for rediscovery and reclamation through a queer lens. Ancient theatrical traditions that forced men into playing female roles has always been a milieu ripe for such themes, but rarely has it been done as delicately and with as much nuance as it is in Farewell My Concubine, a tale in which gender roles and sexuality clash in a world built on tradition and artifice, becoming intertwined with the ever shifting march of time that leaves little time for personal truth. It's an operatic tragedy on a truly grand scale.